Understanding Facial Eczema in Dairy Cattle

Facial Eczema (FE) is a liver disease in ruminants caused by the mycotoxin sporidesmin, which is produced by the fungus Pithomyces chartarum. This fungus thrives on decaying pasture litter when moisture and temperature conditions are favorable, usually during the late summer months. Sporidesmin can affect cattle even when exposure to the fungus is minimal. The condition is most commonly observed to start from late January to early February, particularly when the nights are warm and humid (above 12°C) or when a dry period is followed by rainfall.

The Role of Zinc in Protecting the Liver

Zinc plays a critical role in preventing liver damage caused by Facial Eczema. It helps protect liver cells from the toxic effects of sporidesmin. Without sufficient zinc, the liver cells become more vulnerable, and the bile ducts may become blocked. Therefore, maintaining adequate zinc levels in cattle is essential to reduce the risks associated with FE.

When Does the FE Season End?

The FE season generally concludes when night temperatures consistently drop below 12°C. To confirm the end of the season, continue monitoring spore counts until they consistently fall below 10,000 spores per gram of pasture for three weeks. In some regions, the FE season is changing and may start as early as November or December, while in others, spores can still be present in June. It’s crucial to monitor spore counts regularly to assess the risk accurately.

Tips for Managing and Preventing Facial Eczema

- Avoid the Following:

- Grazing pasture below a 4 cm height during the summer months.

- Letting dead pasture litter build up, as this can increase spore production (avoid topping pastures that contribute to this).

- Encourage the Following:

- Provide alternative pasture types like chicory, plantain, or turnips, and supplements such as silage, hay, meal, PKE, and maize silage.

- Grazing in exposed, windy areas can reduce spore levels compared to sheltered regions.

- Monitor Spore Counts Regularly: Your farm may have different spore levels than neighbouring farms, so it’s essential to track your own spore counts. Start monitoring when regional spore counts reach 20,000 spores per gram of pasture. Test weekly to understand your specific FE challenge. Monitoring can be done through pasture sampling or faecal testing to track spore ingestion levels.

- Timely Zinc Dosing: Begin zinc dosing early, rather than waiting until spore levels are high. Ensure that the dosage is appropriate for the weight of the animals. Remember that dry stock (non-lactating animals) may not drink enough water to get sufficient zinc via the water trough system, so zinc supplementation is vital.

Zinc Boluses for Long-Term Protection

The most effective form of protection against FE is administering a long-acting intra-ruminal zinc bolus, which provides protection for 4 to 6 weeks. Zinc binds with the toxin and prevents it from causing liver damage. Make sure to give the correct dosage based on each animal’s weight. Without adequate zinc, the toxin can still harm the animal.

Fungicide Spraying: An Additional Measure

Spraying fungicide on pastures can help reduce the risk of FE but is most effective when pastures are actively growing and spore counts are below 20,000 spores per gram of pasture. It’s important to use fungicide in combination with other preventive measures.

Avoid Copper During the FE Season

Copper treatments should be avoided during the FE season or until the zinc has cleared from the animals’ systems. Copper interferes with zinc absorption and can worsen the effects of sporidesmin.

Many local veterinary practices offer free or low-cost pasture spore testing services, and NZ Grazing provides Techion faecal testing kits to make it easier for farmers to monitor spore levels regularly.

The Serious Impact of Facial Eczema

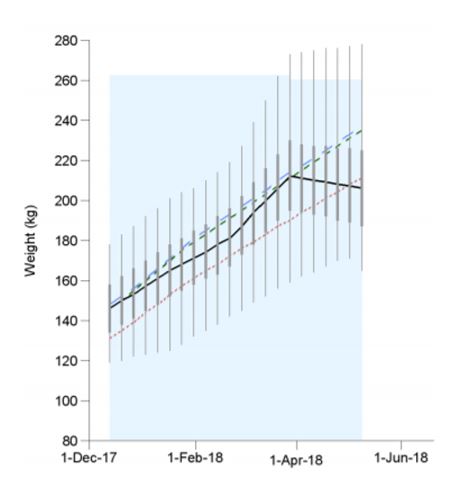

The weight graph below illustrates the significant weight loss and overall poor health that can result from FE without proper zinc protection. In severe cases, FE can even lead to death. Protecting cattle from FE is crucial, especially since there has been minimal genetic selection for FE tolerance in dairy cattle.

It’s important to remember that for every animal with visible symptoms of FE, there may be several others affected but showing less obvious signs. The unseen production losses are often far greater than those that are immediately apparent.

Common misconceptions amongst some farmers.

- The presence of sun burn or photo-sensitivity means FE has broken out and the animal is starting to recover.

Fact:

Photo-sensitivity is a classical symptom of FE. It is the result of the damaged liver’s inability to break down and inactivate the photo active substance of plants, called chlorophyll. When this builds up in the blood stream and circulates through the skin, it reacts with sunlight, causing tissue damage and intense inflammation!

- Dark skinned solid coloured animals are genetically resistant to FE.

Fact:

The dark skin pigment, melanin, protects these animals from getting the photosensitisation or sunburn. But they are just as susceptible to getting FE as animals with white skin and may display other symptoms such as diarrhoea, weight loss, reduced milk production, droopy ears, red or in severe cases, jaundiced conjunctiva/sclera.

- A pregnant cow, with FE induced liver damage, is able to compensate by utilising the liver of the foetus.

Fact:

The blood of the mother and foetus do not mix. Only nutrients, oxygen and some smaller molecules cross the placenta. It is the dams liver, that performs some 500 different physiological functions to keep her and the foetus healthy and growing. The foetal liver is not fully functional until birth.

By taking the proper steps to manage and monitor Facial Eczema, you can protect your dairy cattle and minimize the risks associated with this dangerous disease.

Editing and common misconception acknowledgments Dr Jacquie Lorenz, BVSc

Words by Bridget Clark, Operations Manager.